The country’s aspiring writers are aiming to make a big splash at the world’s largest book festival next year.

Did you know a literary renaissance is taking place right here in Indonesia? Last year, organizers of the Frankfurt International Book Fair, the largest book fair in the world, took note, and next year, Indonesia will be the fair’s guest of honour, a unique opportunity to showcase its writers to an audience of over 300,000 attendees and thousands of international media. In fact, this is the first time a Southeast Asian nation has ever been selected for the honour.

The reason why is simple: Indonesia has, since its emergence as a democracy 16 years ago, become one of the world’s most vibrant literary markets, with the number of titles published per year more than tripling from 6,000 to 30,000. Few ever make their way outside of the archipelago due to institutional, cultural, and linguistic barriers. That might finally be changing. If all goes well, next year the world will be introduced to this country’s dynamic, young voices.

The reason why is simple: Indonesia has, since its emergence as a democracy 16 years ago, become one of the world’s most vibrant literary markets, with the number of titles published per year more than tripling from 6,000 to 30,000. Few ever make their way outside of the archipelago due to institutional, cultural, and linguistic barriers. That might finally be changing. If all goes well, next year the world will be introduced to this country’s dynamic, young voices.

Emerging from darkness

During the Suharto era, Indonesia was subject to draconian restrictions on freedom of speech and expression. Strict publishing permitting rules left little space for writers to explore new topics. Challenging the government became reason for repression, as the case of Indonesia’s most well-known modern writer, Pramoedya Ananta Toer, whose socialist leanings and critical writing led to his imprisonment. His most famous work, The Buru Quartet, was initially told orally while he languished in Buru Island prison, where, for years, he was not even allowed access to pen and paper.

In the 16 years since Suharto’s fall in 1998, Indonesia has undergone a dramatic democratic transformation, and today is often considered the most vibrant democracy in Southeast Asia. Likewise, its literary scene has seen a similar boon.

“Since the fall of Suharto in 1998, numerous writers have changed tactics and adopted a more in-your-face approach,” said John H. McGlynn, Chairman and Co-Founder of the Jakarta-based Lontar Foundation.

Laksmi Pamuntjak, whose book The Question of Red, was just released in English this year, agrees. “The rhetoric of anti-communism as a pretext for state terrorism began to lose its power; consequently it ushered a new thirst for alternative readings not just of the Suharto regime’s myriad misdeeds, but also of the anti-communist massacres of 1965-1966.”

A diversity of stories

In the early years of democracy, writers often floundered, unable to find their footing or voices. Today, according to Pamuntjak, new authors and styles are flourishing. “We have some wonderful authors with distinctive voices: there are the novelists Oka Rusmini, Leila S. Chudori and Eka Kurniawan, the poets Nirwan Dewanto, Joko Pinurbo, Afrizal Malna and the short story writers A.S. Laksana, Intan Paramaditha and Avianti Armand.”

In the early years of democracy, writers often floundered, unable to find their footing or voices. Today, according to Pamuntjak, new authors and styles are flourishing. “We have some wonderful authors with distinctive voices: there are the novelists Oka Rusmini, Leila S. Chudori and Eka Kurniawan, the poets Nirwan Dewanto, Joko Pinurbo, Afrizal Malna and the short story writers A.S. Laksana, Intan Paramaditha and Avianti Armand.”

Another example is Okky Madasari, whose Khatulistiwa Literary Award winning novel Maryam explored how followers of religious minority group tries to survive from the oppression of the majority and mainstream view. Such a daring topic would have been unthinkable before 1998, and shows how far the country has moved in such a short time period.

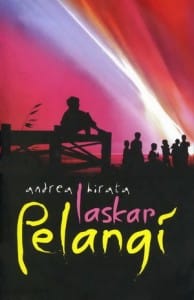

The most well-known contemporary Indonesian author is Andrea Hirata, whose novel Laskar Pelangi has been translated into 19 languages and was made into a popular film, still one of Indonesia’s highest grossing films ever. Hirata believes that his success is opening the door for more of his fellow citizens to tell their stories to eager global audiences.

So, besides Hirata, why hasn’t Indonesia’s literary renaissance yet made waves abroad?

One reason is Indonesia’s relative obscurity globally. This means that Indonesian culture – including its vast diversity – is unknown in the countries that dominate global publishing.

Adding to the challenge is that the world’s top markets, the United States and the United Kingdom, don’t leave much market space for translated literature. According to the University of Rochester’s translation program, only a paltry 3% of literature book sales in the United States market are of translations, and even that is dominated by a few well-known global authors like Harumi Murakami or Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

However, Kate Griffin, the International Programme Director at the British Centre for Literary Translationbelieves that new opportunities are opening for writers. “The number of books published in translation has been increasing steadily in the UK. This means that it’s a good time for Indonesia to be promoting its literature to publishers in other countries,” adding that her organization has been working directly with Indonesian writers and publishers to bring their works to new markets. Moreover, Griffin believes that Indonesia’s designation at Frankfurt could be a turning point, citing the government’s efforts to translate works ahead of the festival.

For the sake of this country’s young, inspiring authors, let’s hope that Griffin is right. If all goes well, and Indonesia’s government builds on Frankfurt, perhaps in the coming years, we’ll see more Indonesian works available in different languages at international bookshops around the world.