This is Ambon in the early 80s of last century. The land we were going to build houses on was located at Karangpanjang, just below the Provincial Parliament Building.

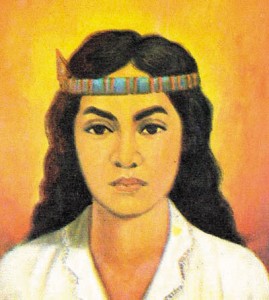

And there, guarding over the parliamentarians, is a large statue. An imposing woman, proudly straight-backed like the spear she holds, her hair fanning out behind her as she gazes at Ambon Bay and the Banda Sea beyond.

“WHO’S THE STATUE?” I asked when inspecting the land. “Martha”, was the short answer. “What did she do to deserve a statue?” “She fought you lot… together with Pattimura!”

That answer came with a wide grin. The night before we had had a couple of beers together and in the process had become well acquainted. He had told me about his family in Holland who had, only a few months ago, come on a visit. After the RSM-in-exile had promised not to hijack trains again and neither to occupy Indonesian consulates or other buildings, restrictions on visits by Dutch-Ambonese to the Moluccas were lifted. And that was also the reason that, in the context of Dutch International Cooperation, the Maluku Project had been started.

Pattimura I knew. Pattimura, a sergeant major in the British army, had been angered by the decision of the Dutch (reinstated in 1816 after the British Interregnum) to discharge him and his fellow soldiers. He refused to accept the restoration of Dutch colonial power. He was afraid that, just as had been done in 1810, native Christian teachers would not be paid anymore, and that the intended switch to paper currency would starve the churches of alms—only coins were considered valid.

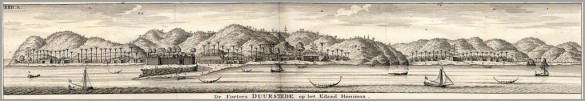

But Martha Christina Tiahahu was new to me. She and her father, I learned, had joined Pattimura and had on 16th May 1817, participated in the conquest of the Duurstede fortress on Saparua.

They had killed all Dutchmen inside the fortress; only the five-year-old son of the Resident, although severely wounded, had survived. After having been taken care of by Salomon Pattiwaal, a servant of the Van den Berg family, the boy was returned to the authorities and to his (distant) family in Holland. In 1875, a Royal decree granted the boy the right to change the family name to “Van den Berg van Saparoea” in remembrance of the 1817 event.

Martha was born on 4 January 1800, and died on 2nd January 1818. She was brought up by her father, Captain Paulus Tiahahu of the Soa Uluputi clan, as her mother died when she was still an infant. She has been described as strong-willed and stubborn, following her father everywhere, even when planning an attack. With her father she joined the guerrilla war against the returning Dutch colonial government, backing Pattimura.

In the light of what happened during the first half of the 20th century, when Ambon and the Ambonese were the favourites of the Dutch administration, and Maluku was called the 12th province of the Netherlands, this revolt is rather unusual. I can only explain it in the following manner. The Dutch were probably less than keen on the region, as its spices—cloves, nutmeg and mace—were no longer the prime reason for being in the archipelago. The necessary austerity measures, or was it the infamous Dutch stinginess, had once already led to terminating payments to the native Christian teachers; and printing paper money was easier and cheaper than the mintage of coins. The decision makers in Batavia would most likely not have known about the need for coins to pay alms. But for the region’s inhabitants, this was an issue of paramount importance. I remember that when my project needed day labourers to collect soil samples, it was difficult to interest anybody to pick up a shovel at the offered rate of five thousand rupiah (in those days a princely sum). Only when we offered the same five thousand, but split into four-andhalf for the church and 500 for the labourer himself, did we get more manpower than we could handle.

In the light of what happened during the first half of the 20th century, when Ambon and the Ambonese were the favourites of the Dutch administration, and Maluku was called the 12th province of the Netherlands, this revolt is rather unusual. I can only explain it in the following manner. The Dutch were probably less than keen on the region, as its spices—cloves, nutmeg and mace—were no longer the prime reason for being in the archipelago. The necessary austerity measures, or was it the infamous Dutch stinginess, had once already led to terminating payments to the native Christian teachers; and printing paper money was easier and cheaper than the mintage of coins. The decision makers in Batavia would most likely not have known about the need for coins to pay alms. But for the region’s inhabitants, this was an issue of paramount importance. I remember that when my project needed day labourers to collect soil samples, it was difficult to interest anybody to pick up a shovel at the offered rate of five thousand rupiah (in those days a princely sum). Only when we offered the same five thousand, but split into four-andhalf for the church and 500 for the labourer himself, did we get more manpower than we could handle.

It would thus appear that the uprising had a religious tint, and that an important reason was the fear that the church would suffer. But on the other hand, Pattimura, Martha and their band of revolutionaries cannot be considered a major general uprising. Their numbers were not that large, and they were moreover from Saparua. The larger and more important island of Ambon was represented by a token few fighters only, and the island of Haruku participated even less, as its population was largely Muslim.

The lack of general support can also be deduced from the fact that Pattimura was betrayed by Pati Akoon, the Raja of Booi, on Ambon. He was taken prisoner by the Dutch on 11th November 1817 together with Martha, her father and many of their comrades. Pattimura was sentenced to death and one month later was hanged in Ambon. Martha’s father was executed on Nusalaut, but because of her age, Martha herself was freed and sent home. Maybe with a pat on the head and the admonition not to play war with grownups again.

This disparaging treatment must have insulted the revolutionary soldier. She had fought with a musket and, when ammunition ran out, had picked up a spear and thrown rocks at the enemy. As could have been expected, she continued fighting and was recaptured within a short time. Now there was no pat on the head and a warning. She was condemned to slave labour on the coffee plantations of Java. Interestingly, Raffles’ biographers have for a long time claimed that he, the famous founder of Singapore, abolished slavery in the East Indies, but in fact it was trading in slaves that he forbade. To sentence someone to slave labour was thus still within the law.

The girl who, since early childhood, had lived in a soldiers’ community and had most probably dreamt of great achievements and liberating the islands from the foreign oppressor, was now chained in the brig of the Admiral Evertsen on her way to Batavia. With her freedom taken and her dreams shattered she fell ill. Refusing medication and food, she died on 2nd January 1818 and that same day was given a burial at sea.

In commemoration of the day, 2nd January has been declared Martha Christina Tiahahu Day.