Daniel Pope remembers some of his international comings and goings.

In 1986, while the cold war was still going on, I entered East Berlin from the west side of the city through the famous Checkpoint Charlie crossing point. My passport, which had been issued during a brief spell in the British military in my youth, listed my original occupation as ‘government service’, not that I was ever much of an asset to Queen and Country. My rifle range instructor had remarked that I was about as lethal as a packet of pork sausages.

Stuffed down my sock was a wad of East German marks – exchange rate differences made smuggling currency into the country more lucrative than obtaining it inside, although this practice was illegal. I stood anxiously at a booth while the border guard examined my passport.

“Government service, ya?” His lips smiled, his eyes didn’t.

I pointed out that this suspicious occupation had been officially struck out on my passport with a single line of red ink, and ‘musician’ written underneath. I was an unemployed beatnik guitar player in those days (deep down I still am). Even so, I imagined that the guard had already pressed a button under the counter, prompting a nearby covert agent to turn up his collar and start tailing me through the streets during my day-trip to East Berlin.

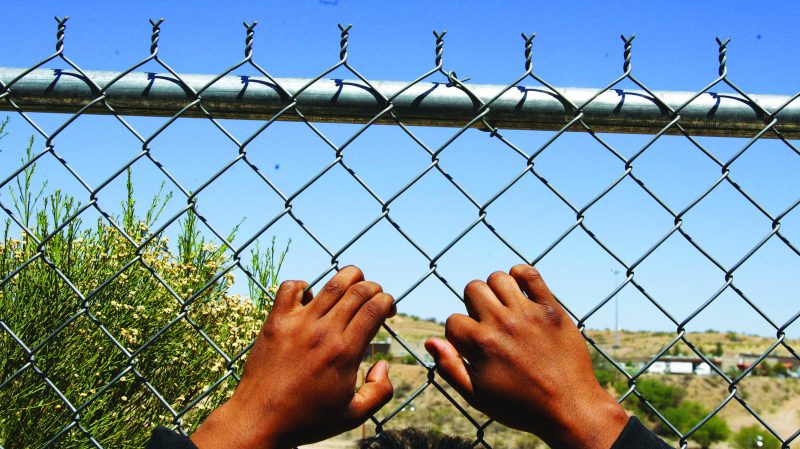

Crossing any kind of border checkpoint can be fretful. I’ve passed through Indonesian immigration control many times quite lawfully, but still find it an ordeal.

In the old days, I used to enter the country through Batam or Bintan islands, as these were ‘backwater’ places whose staff seemed easier to deal with. At Jakarta’s Soekarno-Hatta international airport it was a different matter. “Awas” (beware) an immigration officer had once snarled at me after a fruitless ten minutes of trying to find an irregularity in my papers.

But the smaller border crossings weren’t always the smoothest ones. I once arrived at Johor Bahru ferry terminal after travelling around Southeast Asia in 2004, at the height of a Malaysian campaign to deport thousands of illegal Indonesian domestic workers. After finally squeezing down the gangplank onto the ferry, I sat down to wait for the deck to fill up with disgruntled ex-labourers and drivers and their piled boxes of luggage, claiming my bit of seating space.

However, a kindly crew member ushered me into a roomy cabin with soft lounges, which was occupied by a handful of Malaysians on their way to play golf in Batam. Even better, a loudspeaker announcement invited the occupants of this cabin to disembark ahead of the main throng of passengers once we had reached our destination.

Transferring from the ferry port to the airport, I flew from Batam to Jakarta on business class, a first for me. But on this particular airline, which I’d flown with on the cheap many times before, the only difference between business class and economy class, apart from a bit of extra leg room, was that the orange juice was served in a glass instead of a carton, and the currant bun came on a plate and not in a cardboard box.

An advantage of an airport arrivals lounge is that there are no duty-free shops to distract you. There are two types of goods that I find it hard to walk past without taking a closer look. One of those is booze, the other is electronics. Though if you’re after a cheap smartphone in Jakarta, don’t waste your time at the airport. There is a superior option in the city.

I always imagine that umpteen years ago on Jalan K.H. Hasyim Ashari in West Jakarta, a lone trader – an advance forager if you like – set up a stall selling mobile phones. The next day, a passer-by asked him how business was going and, receiving an encouraging response, erected a stall next to his, also selling mobile phones. Next day it happened again – another trader wandered up, unpacked a tarpaulin and a few Nokia handsets, and joined in.

After several weeks of this expansion, the entire area brimmed with mobile phone sellers, who were beginning to clamber over each other like worker ants. The only way to accommodate further vendors, who streamed from the horizon, was to build upward. And so a first floor was hammered into place, then a second, and so on, until eventually a gigantic shopping mall had formed on the spot – seven bustling floors devoted to a single product and its accessories. This might be how Roxy Mas was born.

Cities the world over have streets where traders of similar goods all group together to slug it out, though Jakarta seems to have more than most. One that I passed through every morning on my way to work was a fruit-and-vegetable street in Kemangisan, and for a long time it was an uneventful journey. That was until the day I was attacked by an apple.

My paranoia level on that particular day was high because this was the morning after the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York in 2001 (which I had watched on TV in a bar in Jalan Jaksa). I was uneasy when I left for work that morning – feeling that the world was a more perilous place, more acutely aware of being a Westerner in a far-away land where the natives might turn hostile at a moment’s notice.

But all was quiet until I passed down the fruit-and-veg street in my taxi, and an apple suddenly thudded against the side window, startling me. Convinced that I was under attack, I ordered my driver to speed up, peering through the rear window at the receding bright colours of the fruit and vegetable stalls.

The apple, which I fancied I had recognized as a Royal Gala as it bounced off the glass pane, most probably had been thrown up from beneath the wheels of another vehicle, and not lobbed by a local radical seething with homicidal hatred for all foreigners. But I still contend to this day that someone tried to assassinate me with an apple as I drove along that street. And what’s more, that person is still out there.

My paranoia can be better appreciated if I relate another incident. I had been standing on a corner at Thamrin in Central Jakarta (the exact same spot that earlier this year witnessed a genuine terrorist atrocity) trying to flag a taxi down, when I noticed a demonstration coming toward me along the road. I thought nothing of it – I’d got entangled in demos before and had never felt threatened. In fact, the participants had usually been friendly and simply wanted their photo taken with me.

But with a sudden roar, this crowd of around two hundred people lowered their banners and charged directly at me, shouting and waving their fists in the most hostile manner. To say that I gulped would be to say that Krakatau went ‘pftzz’ in 1883. It was certainly fortunate that I had already visited the lavatory. Otherwise I might have lifted off like a rocket on a plume of my own explosively evacuating bowel contents. I froze, waiting for the apples to start raining down on me. I was dead. I was sure of it.

However, I checked over my shoulder and realized with a whimper of relief that I wasn’t the target of this enraged mob after all. I was standing right in front of the gate to the United Nations building, where the marchers intended to stage some kind of political protest. Even so, I hurried away across the nearby pedestrian bridge, wondering whether I should keep on going until I reached the nearest border crossing.