![]()

![]()

I started with what happens when we flush the loos, yes we have two, in Jakartass Towers. There are certainly no sewers in our area, there’s no evidence that the effluence goes into the got (drainage ditch) in front of our rented abode, so maybe our effluence goes into next door’s septic tank. I really don’t know.

I checked with Flush Tracker (http://flushtracker.com/) but discovered that it doesn’t operate in Jakarta. Mind you, it’s salutory to discover that His Holiness the Pope doesn’t rely on divine intervention for all his ablutions.

So, what does happen to our fecal waste?

According to the Ministry of Public Works, in 2008 20% of Jakartans did not have access to a toilet, forcing them to use whatever space they could find: 1.46 million households disposed of raw sewage into closed gutters and 784,568 dumped it into open gutters which all feed into rivers and canals, while 56,139 households flushed their waste directly into the ground or nearby rivers and canals.

In 2009, Nugroho Tri Utomo, head of the sanitation development technical team at the National Development Planning Board (Bappenas), said that 714 tons of human waste go directly into the ground or waterways each day without being processed.

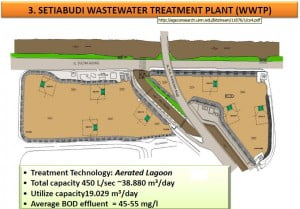

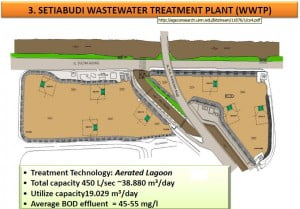

Yet according to the plant operator, PD Pam Jaya, although the total capacity of the plant is 38,880 m3 per day, it only processes half that.

(There are also waste treatment plants in Pulo Gebang, East Jakarta, and Duri Kosambi, West Jakarta.)

So, what of septic tanks?

Jakarta has more than one million of them, few of which are regularly inspected for leakage, let alone serviced. Moreover, due to housing density, about 60% of Jakarta’s houses have wells no more than 10 meters away, which means that groundwater becomes contaminated with e-coli and other nasties and local residents suffer from skin and alimentary complaints.

This leads to the question of why successive City Hall regimes have allowed this to happen? The short answer is that they’ve been in thrall to property developers rather than Jakartans.

In 2005, the former Governor of Jakarta, Sutiyoso, issued the Domestic Waste Water Regulation (PERGUB No. 122 – 2005), which states that households, public infrastructures, and commercial buildings must provide domestic waste management systems, to ensure the effluent produced complies with Government Standards. However, the regulation failed to anticipate the growing urban population and the corresponding issues with access to sanitation in densely populated urban areas.

Jakarta’s shopping malls are busiest at weekends, yet few visitors are there to spend their hard-earned cash. Sutiyoso suggested that for recreational reasons Jakartans preferred their air-condition splendour to the open spaces they’d been built upon. I think he was wrong: surely it is because visitors can spend a penny in clean-ish splendour. And this also begs the question of how malls dispose of their fecal offerings.

In 1997, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Human Development Index (HDI) ranked Indonesia at 106 out of 176 countries.

President Habibie took heed and on the 1st of March 1999 proclaimed the far-reaching ‘Development Movement with Health Concerns in order to materialize Healthy Indonesia 2010’. Six months later, Prof. Dr. F.A. Moeloek, his Minister of Health, issued a 76 page document, with input from most government departments, which covered an extensive range of health issues which determined 10 prioritized programs and a number of targets.

However, sanitation and the disposal and treatment of human waste isn’t one of them; there is only one mention of ‘sanitary toilet’ and ‘closet’, the latter admittedly with the target of “meeting healthy requirements and their utilization to 100% either (eh?) at urban or rural areas” (p.33).

(Priority 8 is an “anti tobacco, alcohol and hashish program”, so there are 19 mentions of ‘narcotics’, 8 ‘addictive’, 6 ‘hashish’ and 2 ‘psychotropics’.)

The instruction and campaign of hygiene and sanitation is mentioned once, yet earlier this year the Indonesia Infrasturucture Initiative reported that “most of the public toilets in Indonesia are still far from being clean because the operators do not quite know how to manage toilet sanitation.”

In 2011, last year, UNDP placed Indonesia at 124th out of 187 countries last year, a drop of 6% in ‘standards’ since 1997.

So what can be done? It is already too late to install a city-wide sewage system; besides, one estimate is that it would cost the city half its annual budget until completed. The answer, therefore, lies with locally managed projects, with trained paid staff.

Examples

NB. 22 million Indonesians have to pay for the use of communal latrines, yet few have DEWATS.

Advice for expats: http://expat.or.id/info/watertreatment.html

*Next year’s World Toilet Summit will be held in Surakarta due to the city administration’s awareness of creating decent public toilets. Its former mayor, Jakarta’s new elected Governor Jokowi, was largely responsible for that.