Through special visas, Sandiaga Uno wants to open the wallets of foreign “digital nomads“, Gen Zedders with laptops in their backpacks and flawless Wi-Fi by the pool.

The Tourism Minister thinks that once among Bali’s palms and paddy they’ll spend their overseas earnings on local services. Whether they’ll leave any positive legacy is another matter.

Before Bali was transformed from a relaxed, magical, and accepting culture to a money machine driven by outside investors, footloose creatives had embraced the island’s rich spirituality. One was Australian John Darling, a young man with a fine education and an assured career.

Despite these advantages, he didn’t have much idea of what he wanted to do and where to go. His university lecturer reportedly advised he’d make “a far greater contribution by increasing Australian understanding of Indonesia through living and researching Bali and other areas of the archipelago.”

As so often happens to open-minded seekers, the purpose found him and it came with a rare culture, an exotic environment and a cine camera.

Now thanks to admirers of John’s thoughtful films, we have a tribute to a contemplator who came to know Bali better than most, accepted what he’d found, and sought to share.

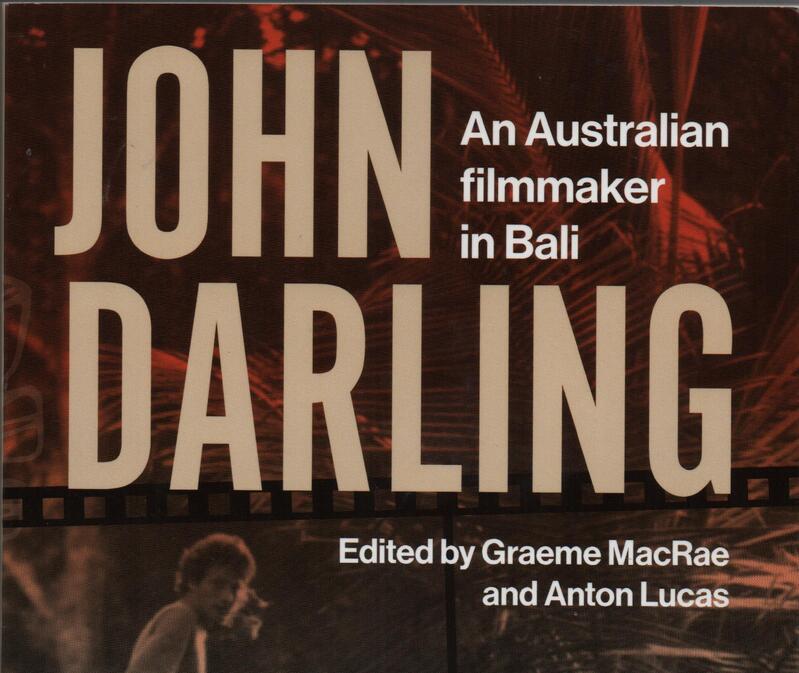

John Darling, an Australian filmmaker in Bali, is a collection of 21 essays assembled by Australasian academics Graeme MacRae and Anton Lucas. There are photos and a few poems:

‘In the mountains / I saw a river/ running rapid

For Buddha /a deep pool/ripples / out from centre

In a quiet place / a fat frog/ croaks content

Trapping his needs / from a flying world.

John was born in Melbourne in 1946 and raised among the elite. His father James Darling was headmaster at Geelong Grammar, one of Australia’s most prestigious schools.

His son’s paved path was heading straight to an academic career, but capricious fate added turns. After uni, John lost his way; his mates suggested Indonesia. He disembarked in Jakarta, slowly bussed east, and then into Bali where serendipity intervened.

According to the book, a revelation came one dawn in a paddy where he met I Gusti Nyoman Lempad the famous Balinese sculptor and artist, then aged 108. He squatted and smoked with a restive Aussie 84 years younger, “seeking a place in which to develop my obscure talents.”

This required celluloid and a mate with technical knowledge. That was to be Lorne Blair, a filmmaker from the UK who became internationally famous for his TV series Ring of Fire, an Indonesian Odyssey made with his brother Lawrence.

Lempad died in 1978 and so began a prolonged set of elaborate funeral rituals that the two outsiders filmed. Because John was an accepted member of the community and could speak Balinese, he had open access to all preparations for the cremation.

Forty-three years later and online, Lempad of Bali has lost little across the decades. It could have been an ethnographic exercise of limited interest outside social anthropology courses, but it was made as a story of interest to all.

That quality helped the producers win the Documentary Award at the Asian Film Festival, and set John’s future not just as a director but also lecturer, writer, and poet.

I worked with him on one film and found him introspective – yet engaging. Some saw him as “shy and very cerebral … a latter-day Romantic poet.” Others report a funny man with “good manners’, and a ‘dashing dandyish figure.”

Toby Miller, a student who became a friend and now teaches cultural studies writes: “Despite his fame, Johnny needed a lot of care – and was himself full of caring love. He was vulnerable and strong in equal parts.”

This assessment helps explain the sensitivity of his films shown on mainstream television internationally including Bali Hash, Slow Boat from Surabaya, Master of the Shadow, Bali Triptych, and Below the Wind.

John’s final work came while he was sick with a genetic disease that took his life in 2011 when he was in Perth. His ashes were sent to Bali.

The Healing of Bali was shot after the 2002 Kuta nightclub blasts which killed 202. There was a rush of journalists to the island, focusing on the event. John’s production concentrates on the survivors and how they are coping with the overwhelming horror.

There’s no foreign voice-over. The people speak for themselves. The grief is raw. The viewer is there.

David Hanan, an Australian film studies lecturer, writes that a major theme of the film “is the lack of discrimination, indeed the underlying warmth of the religiously tolerant Balinese people – including those most impacted by the events – towards local Muslim residents.”

Reviewer David Reeve concluded: “This film is about the healing of Indonesia too, and indeed the world.” His widow and co-producer Sara offers a moving account of the shoot and this tribute:

‘”ohn was a peaceful man who promoted harmony. He related to everyone, from priests to farmers. His films have helped make Indonesia accessible to the world, particularly Australians who so frequently distrust and misunderstand their northern neighbour.”

Digital nomads need this worthy book to appreciate their second home. So do all spellbound by Bali and not led astray by the superficialities of tourism, striving – like John – to see if they fit. And if so, where, how, and why.